6 min read

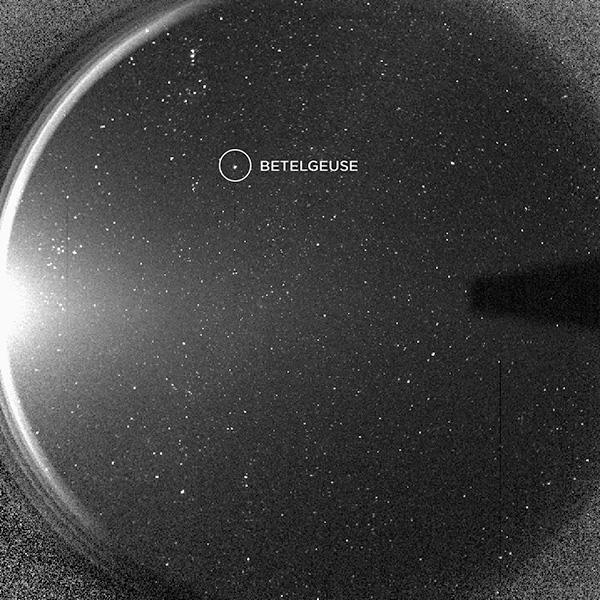

A blazing red supergiant shining brilliantly in the night sky, Betelgeuse is a star that has captured humanity's awe and attention for centuries.

The "right shoulder" in the constellation Orion (or left shoulder, as seen from Earth), Betelgeuse (or Alpha Orionis) is one of the brightest stars in the night sky and one of the largest stars ever discovered. But there is more to this ultra-bright stellar monster than meets the eye.

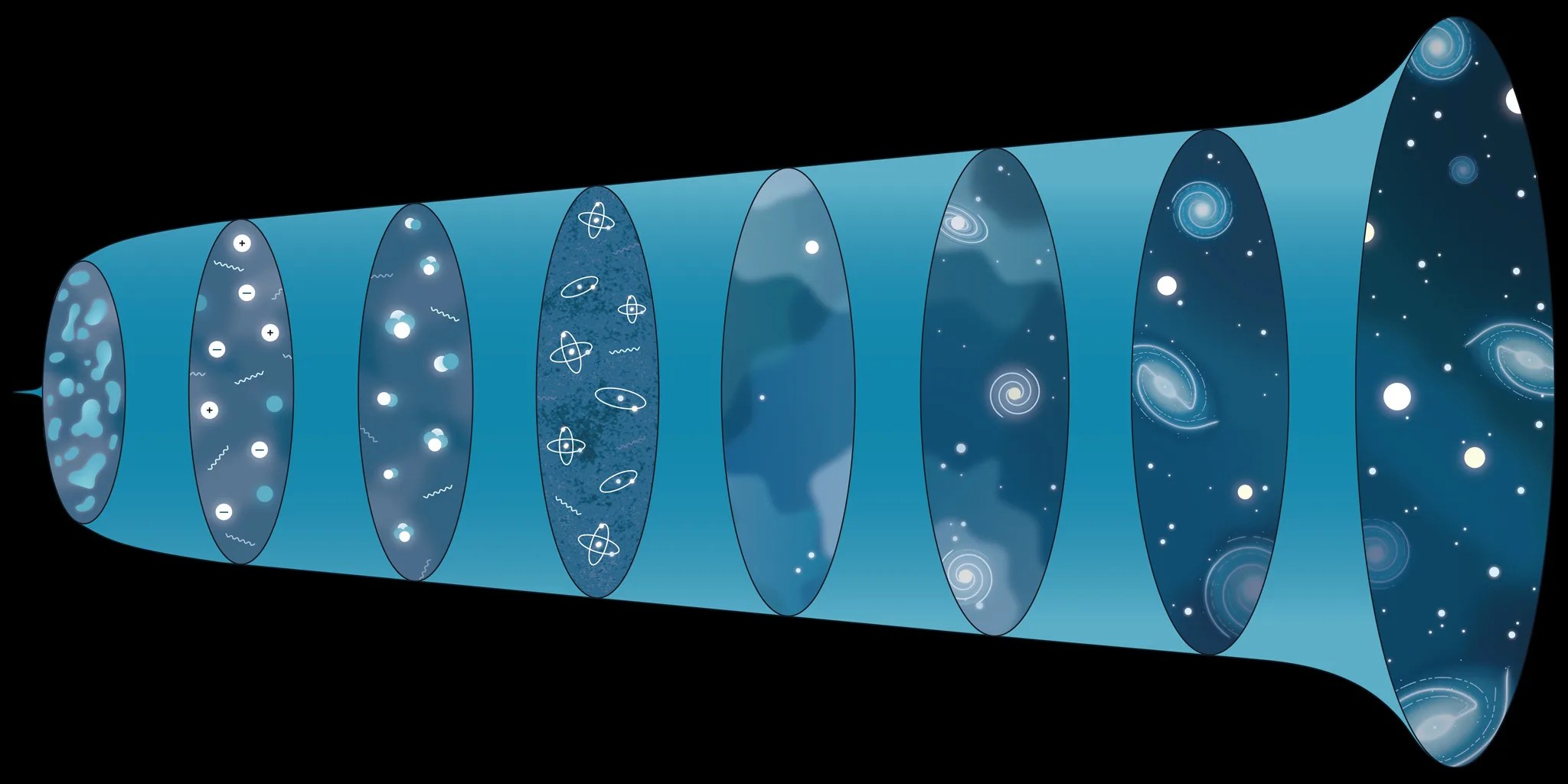

Betelgeuse is a red supergiant star with a distinctive orange-red hue. Stars in this class are nearing the end of their lives. They are the largest stars in the universe because they puff up and expand out into space in their old age.

At roughly 10 million years old, Betelgeuse is much younger than our nearly 5-billion-year-old Sun. But while it is much younger, it is also much more massive and will burn through its materials faster and will therefore have a shorter lifespan than a star like our Sun.

Betelgeuse is around 700 light-years away. This means that it takes the light from this star about 700 years to reach Earth, so if you see Betelgeuse in the night sky, you’re seeing the star from about 700 years ago.

Aside from its unmistakable color, Betelgeuse is particularly easy to spot because of its brightness; it is often the tenth-brightest star in the sky. (It can be much brighter or much dimmer at times.) Betelgeuse is about 7,500 to 14,000 times brighter than the Sun.

Betelgeuse is also one of the largest stars visible to the unaided eye. It’s about 700 times the size of the Sun and around 15 times more massive. In fact, Betelgeuse is so giant that, if we replaced our Sun with Betelgeuse, it would stretch past Jupiter's orbit.

While it is large and bright, Betelgeuse isn't actually that hot, with a surface temperature of about 6,000 degrees Fahrenheit (over 3,300 degrees Celsius) – cooler than our Sun's roughly 10,000-degree Fahrenheit (over 5,500 degree-Celsius) surface.

Because it is so bright and relatively close to Earth, and since it’s possible to see details on the star that are not visible on fainter, more distant stars, scientists have studied Betelgeuse throughout history. Scientists think it's likely that even the earliest humans were aware of Betelgeuse. It is also incorporated in the stories and mythology of many different cultures.

While many refer to the star as part of Orion, named for the hunter in Greek mythology, ancient Egyptians included Betelgeuse in their constellation Osiris, named after their mythical god of the underworld. Ancient Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy is said to have described the star with the Greek word "hypókirrhos," which translates to mean a color that can range from a pale yellow to a light reddish color. This suggests that the star had not yet developed into the more reddish color we are familiar with today.

In 1603, German astronomer Johann Bayer gave the star its Latin name Alpha Orionis, with alpha meaning it’s the brightest star in its constellation. It retains this name, even though the star Rigel is now known to be the brightest in Orion.

In 1836, astronomer and mathematician Sir John Herschel documented Betelgeuse's changing brightness, but he was likely not the first to note it. There is evidence that the variability of Betelgeuse and other red giants was described much earlier in Aboriginal oral traditions.

Betelgeuse has since been classified as a "semiregular variable star," which is a type of variable star that periodically waxes and wanes in brightness and occasionally undergoes irregular light changes. Betelgeuse, typically, has a 400-day cycle as well as a longer cycle that stretches about 5 years. But in 2019, something strange happened.

In the fall of 2019, Betelgeuse started to drastically dip in brightness, outside of its typical brightening and fading cycle. Within months, the star had dimmed by about 60% in an event now known as the Great Dimming.

This sudden dimming was so significant that some scientists wondered if Betelgeuse was entering a "pre-supernova" phase, which precludes a massive star’s explosive “death” in a supernova. Talk of a possible explosion sparked intrigue around the world as Betelgeuse would be the closest supernova to ever be observed and recorded by humans.

By April of 2020, Betelgeuse had returned to its normal brightness. But the dimming remained a mystery. There were early attempts to make sense of the strange and unusual event, but the full picture wouldn't be revealed until the next year.

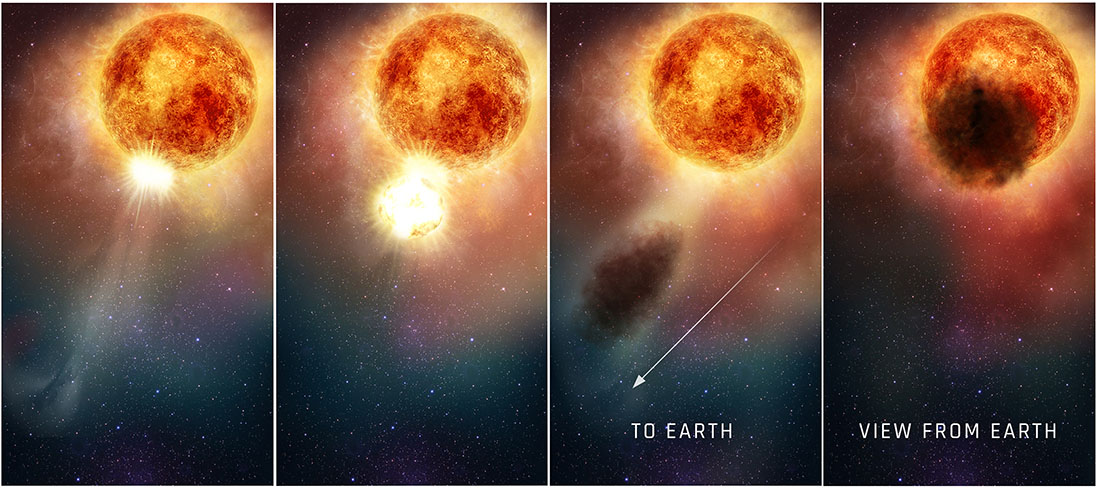

By analyzing data from observatories including NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, scientists found that Betelgeuse "blew its top" in 2019. The star spewed a giant piece of its surface material out into space (a type of event known as a surface mass ejection). Once in space, this material cooled into a dust cloud that temporarily blocked the light from the star.

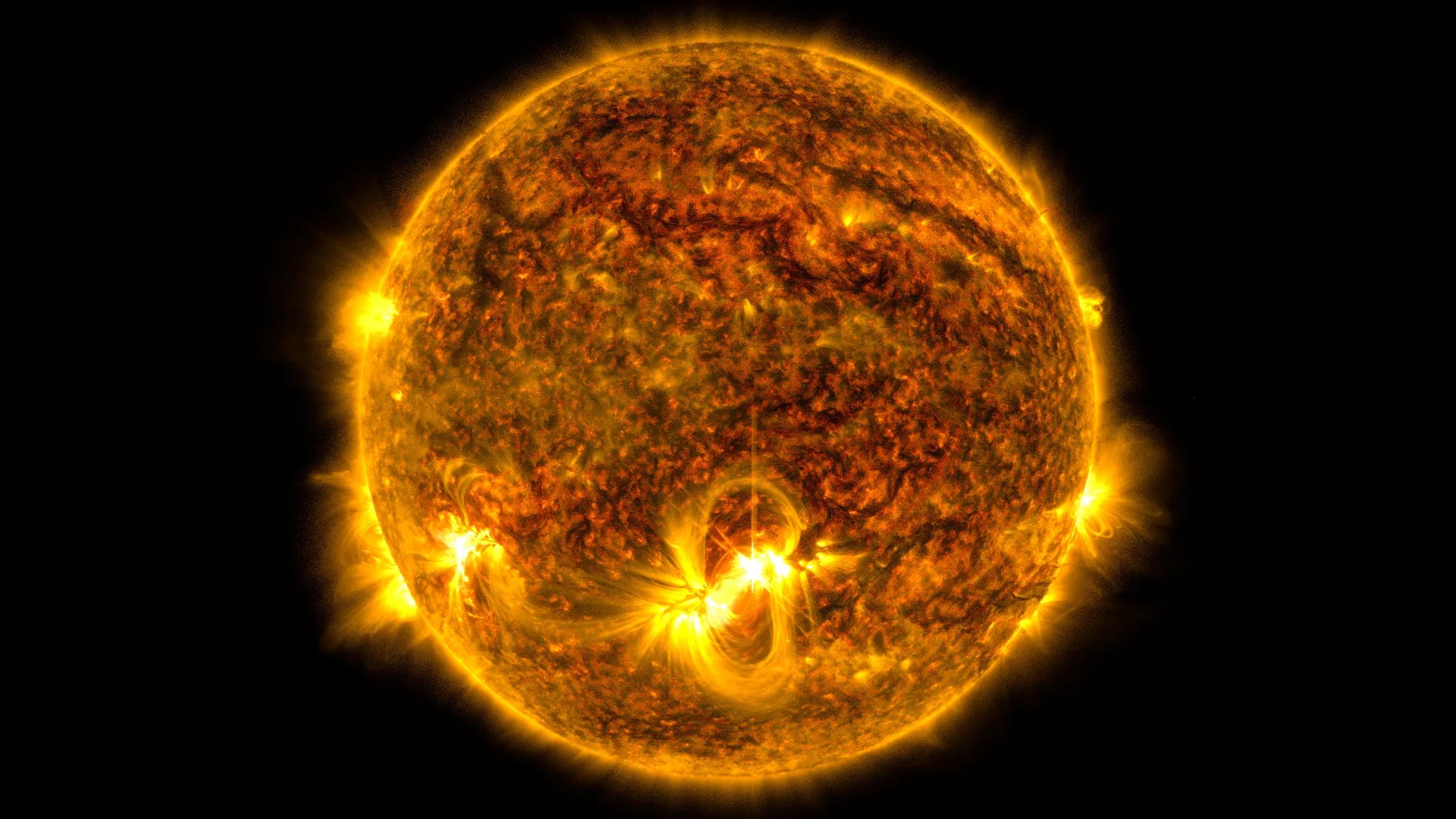

Ejecting material is fairly normal for stars. In fact, our Sun does this routinely, blowing out material from its outer atmosphere, or corona, in events called coronal mass ejections.

But the Betelgeuse eruption was not like the Sun’s routine ejections. Betelgeuse blew 400 billion times as much mass as is usually emitted during a coronal mass ejection, and the chunk it spewed out into space likely weighed several times as much as our Moon.

Scientists think that the massive, never-before-seen ejection was potentially caused by a plume of gas bubbling up from within the star, which was assisted by the star’s normal 400-day pulsation cycle. However, the exact cause and mechanism behind it is still unknown.

As the dust both literally and figuratively settles for Betelgeuse, and it continues to recover from the Great Dimming, scientists have been observing the star and its strange behavior.

While this surface mass ejection is something that humanity hadn't witnessed before, it is possible that ones like this are a relatively common occurrence throughout the universe. The fact that we witnessed it at all with Betelgeuse is due to our familiarity with the star, its closeness and large size, and our ability to observe the entire star in close detail with the Hubble Space Telescope.

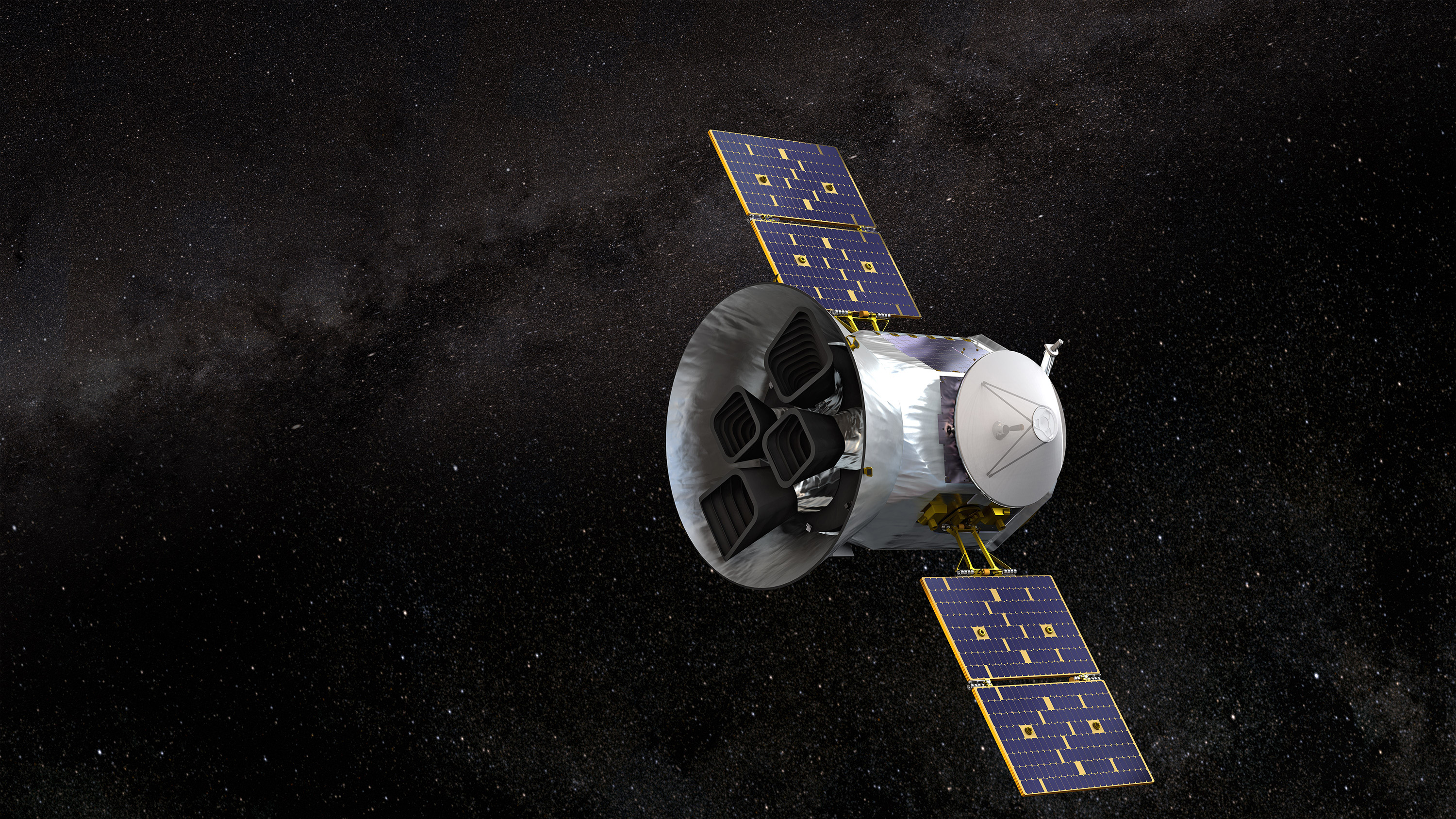

Skywatchers can see Betelgeuse from their backyards, so there are no shortage of observations. However, to get a closer look at the star, its atmosphere, and how it is changing in significant detail, scientists depend on observatories like Hubble.

Hubble’s ability to “see” in ultraviolet light has been instrumental in revealing the details of the Great Dimming and its continued aftermath. By observing it in ultraviolet light, Hubble can get a close look at the hot layers of atmosphere above the star's surface. While Hubble remains a primary tool for scientists exploring Betelgeuse, the star’s future and the evolving ways in which humanity explores this strange star remain open-ended.

The only thing that's certain? Betelgeuse will, eventually, go supernova. However, scientists expect this isn't likely to happen for about another 100,000 years, at which point Betelgeuse will become either a neutron star or black hole. The star’s final fate depends on how much material is left after the supernova event.

By Chelsea Gohd

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory