Types of Galaxies

Scientists sometimes categorize galaxies based on their shapes and physical features. Other classifications organize galaxies by the activity in their central regions – powered by a supersized black hole – and the angle at which we view them.

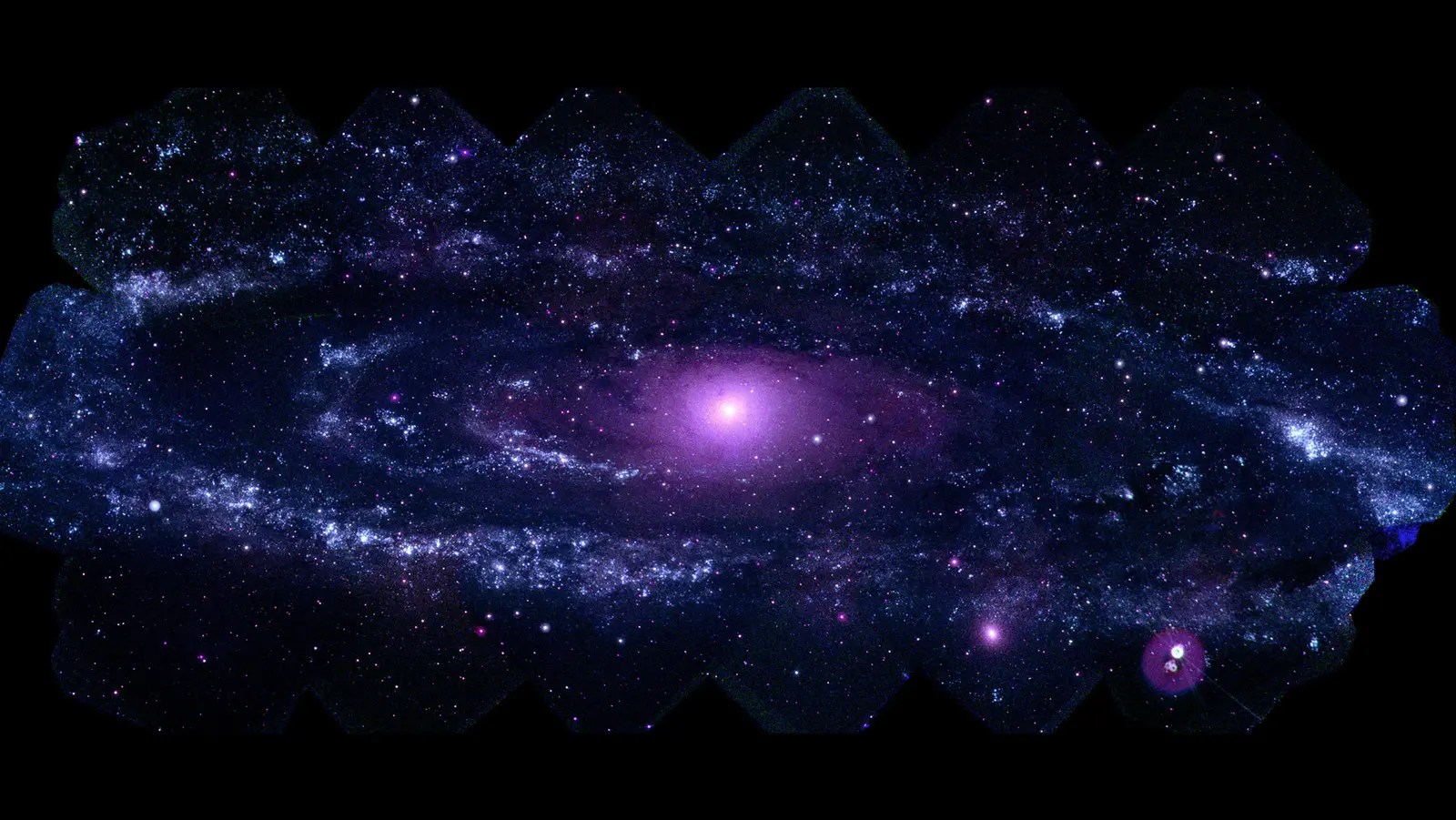

Spiral Galaxies

Our Milky Way is one example of a broad class of galaxies defined by the presence of spiral arms. These galaxies resemble giant rotating pinwheels with a pancake-like disk of stars and a central bulge or tight concentration of stars.

The spiral arms can be wound tightly or loosely, and some cannot be seen from Earth because we view the galaxy from the side, edge on.

Spiral galaxies are surrounded by halos, mixtures of old stars, star clusters, and dark matter – invisible material that does not emit or reflect light but still has a gravitational pull on other matter. The youngest stars form in gas-rich arms, while older stars can be found throughout the disk and within the bulge and halo.

Both the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxies belong to a subtype known as barred spirals, which make up two-thirds of the group. Barred spirals sport ribbons of stars, gas, and dust that cut across their centers. Scientists think the presence of a bar indicates that a galaxy has reached full maturity.

Elliptical Galaxies

Elliptical galaxies have shapes that range from completely round to oval. They are less common than spiral galaxies.

Unlike spirals, elliptical galaxies usually contain little gas and dust and show very little organization or structure. The stars orbit around the core in random directions and are generally older than those in spiral galaxies since little of the gas needed to form new stars remains. Scientists think elliptical galaxies originate from collisions and mergers with spirals.

Lenticular Galaxies

Lenticular galaxies are a kind of cross between spirals and ellipticals. They have the central bulge and disk common to spiral galaxies but no arms. But like ellipticals, lenticular galaxies have older stellar populations and little ongoing star formation.

Scientists have a few theories about how lenticular galaxies evolved. One idea suggests these galaxies are older spirals whose arms have faded. Another proposes that lenticulars formed from mergers of spiral galaxies.

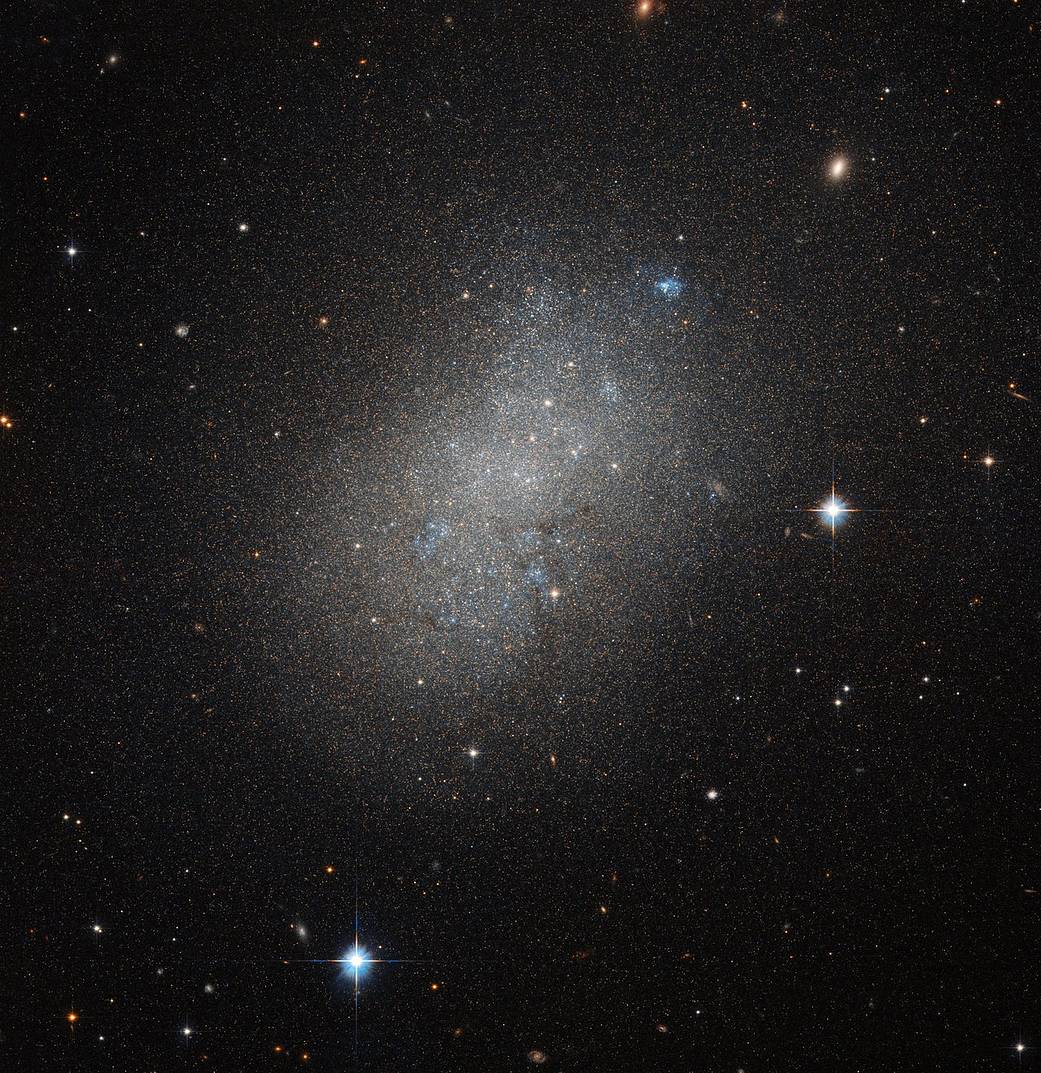

Irregular Galaxies

Irregular galaxies have unusual shapes, like toothpicks, rings, or even little groupings of stars. They range from dwarf irregular galaxies with 100 million times the Sun’s mass to large ones weighing 10 billion solar masses.

Astronomers think these galaxies’ odd shapes are sometimes the result of interactions with others. For example, one spiral galaxy passing another with a stronger gravitational pull could lose some of its material, become distorted, and morph into a new shape. Some, like gas-rich dwarf galaxies, may be new, formed by material pulled from such encounters. Or perhaps when galaxies collide, they create a larger, oddly shaped mashup. Some scientists theorize that some large irregular galaxies could represent an intermediate step between spiral and elliptical galaxies.

Irregular galaxies born from galaxy interactions or collisions typically host a mix of older and younger stars, depending on the characteristics and composition of the original galaxies. Irregular galaxies may also hold significant amounts of gas and dust – essential ingredients for making new stars.

Active Galaxies

Around 10% of known galaxies are active, which means their centers appear more than 100 times brighter than the combined light of their stars. They can be spiral, elliptical, or irregular. The Milky Way is not currently an active galaxy, although it likely experienced a burst of activity in the past few million years.

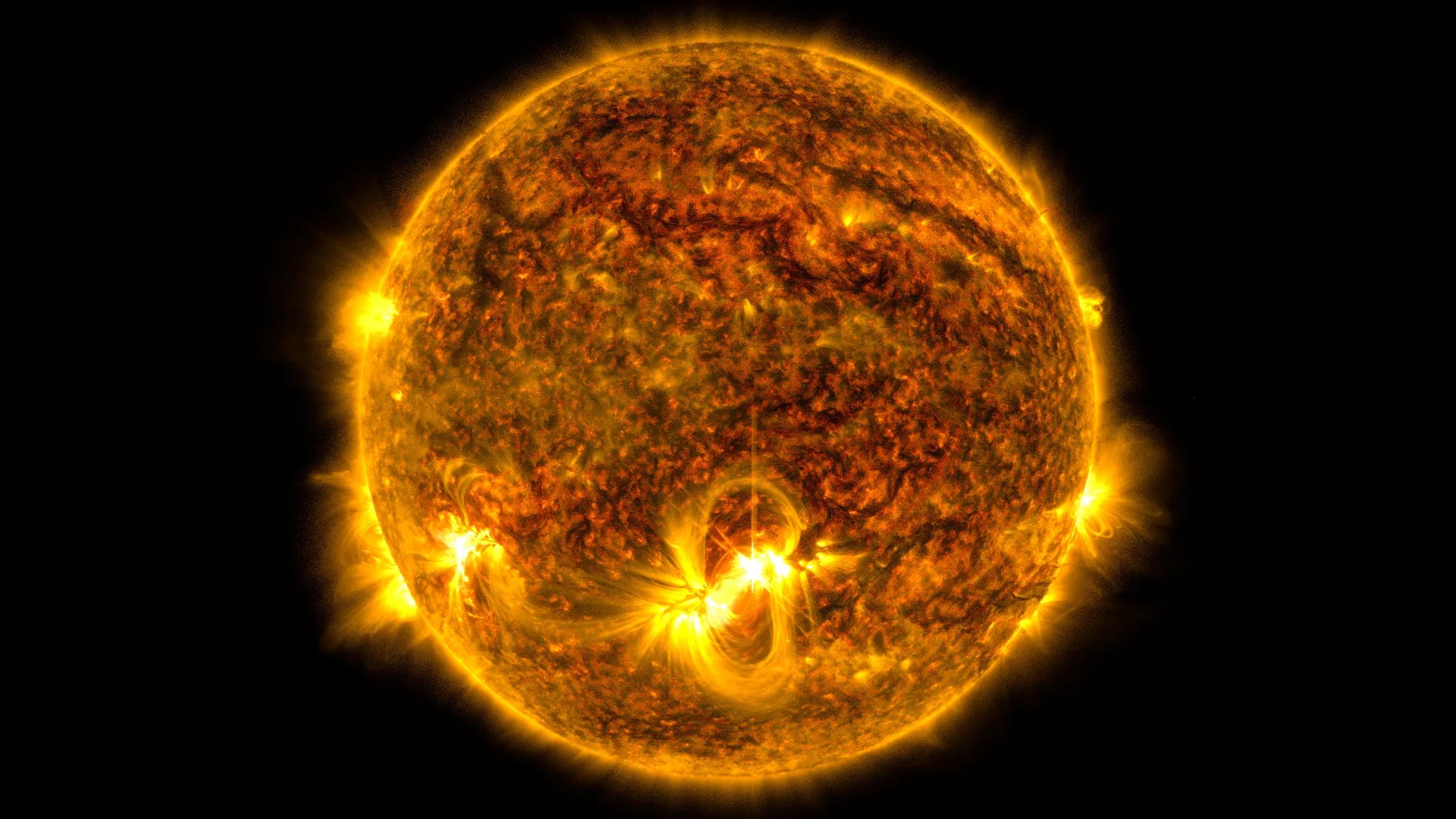

Astronomers think this excess energy comes from areas near the galaxies’ central supermassive black holes, which range from hundreds of thousands to billions of times the mass of our Sun.

Gas and dust collect around the black hole to form an accretion disk. The black hole’s gravity compresses and heats the disk, which causes the material to glow across multiple wavelengths, from infrared to X-rays.

Infrared observations show that the black hole and its accretion disk are embedded within a clumpy ring of cooler dust, called a torus, that may be a few light-years across. Close to the black hole, a small fraction of the infalling gas can be driven outward, perpendicular to the disk, as jets of particles that move near the speed of light.

During the early 20th century, astronomers began classifying active galaxies based on the distinctive characteristics and behaviors they observed. Scientists now think viewing the centers of these galaxies at different angles – for example, seeing directly into the torus versus seeing it from the side – produce many of the signature traits.

Active galaxies can also be categorized by their brightness in radio wavelengths. Radio-loud galaxies typically emit from both the accretion disk and the jets. Radio-quiet galaxies tend to have little-to-no emission from jets. The observed luminosity is also thought to be another aspect of our viewing angle. Jets directed more toward our line of sight, viewed “down the barrel,” appear brighter and more variable than those viewed at wider angles.

Seyfert Galaxies

Seyfert galaxies, first identified in 1943 by American astronomer Carl Seyfert, are the most common active galaxies and also exhibit the lowest energies. All Seyferts look like normal galaxies in visible light, but they emit considerable infrared radiation. When observed in the infrared, some reveal bright emission from the donut-shaped torus. Some also emit X-rays. Seyfert galaxies tend to have lower radio luminosities, although some produce radio jets.

Scientists divide Seyferts into two classes. Type I Seyfert galaxies display unusual features in their visible light that imply rapid motion near the accretion disk. Type II Seyferts show features that imply much slower motion. However, this distinction may result from different viewing angles into the centers of these galaxies.

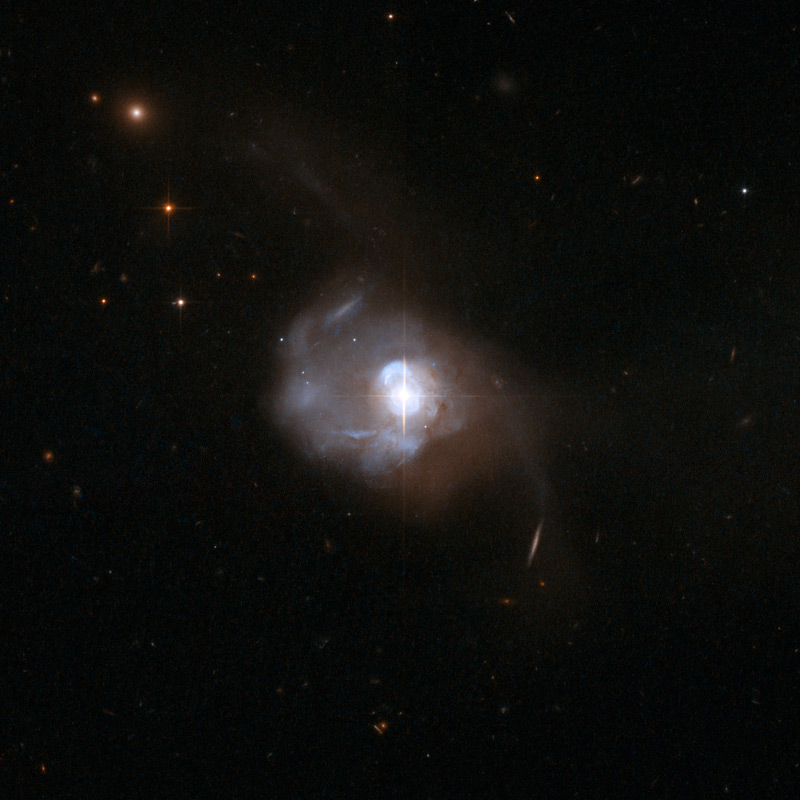

Quasars

Quasars are the most luminous type of active galaxy. They emit light across the electromagnetic spectrum, produce powerful particle jets, and can radiate thousands of times the energy emitted by a galaxy like the Milky Way. The nearest quasar, called Markarian 231, is located some 600 million light-years away, but we see many more quasars the farther we look.

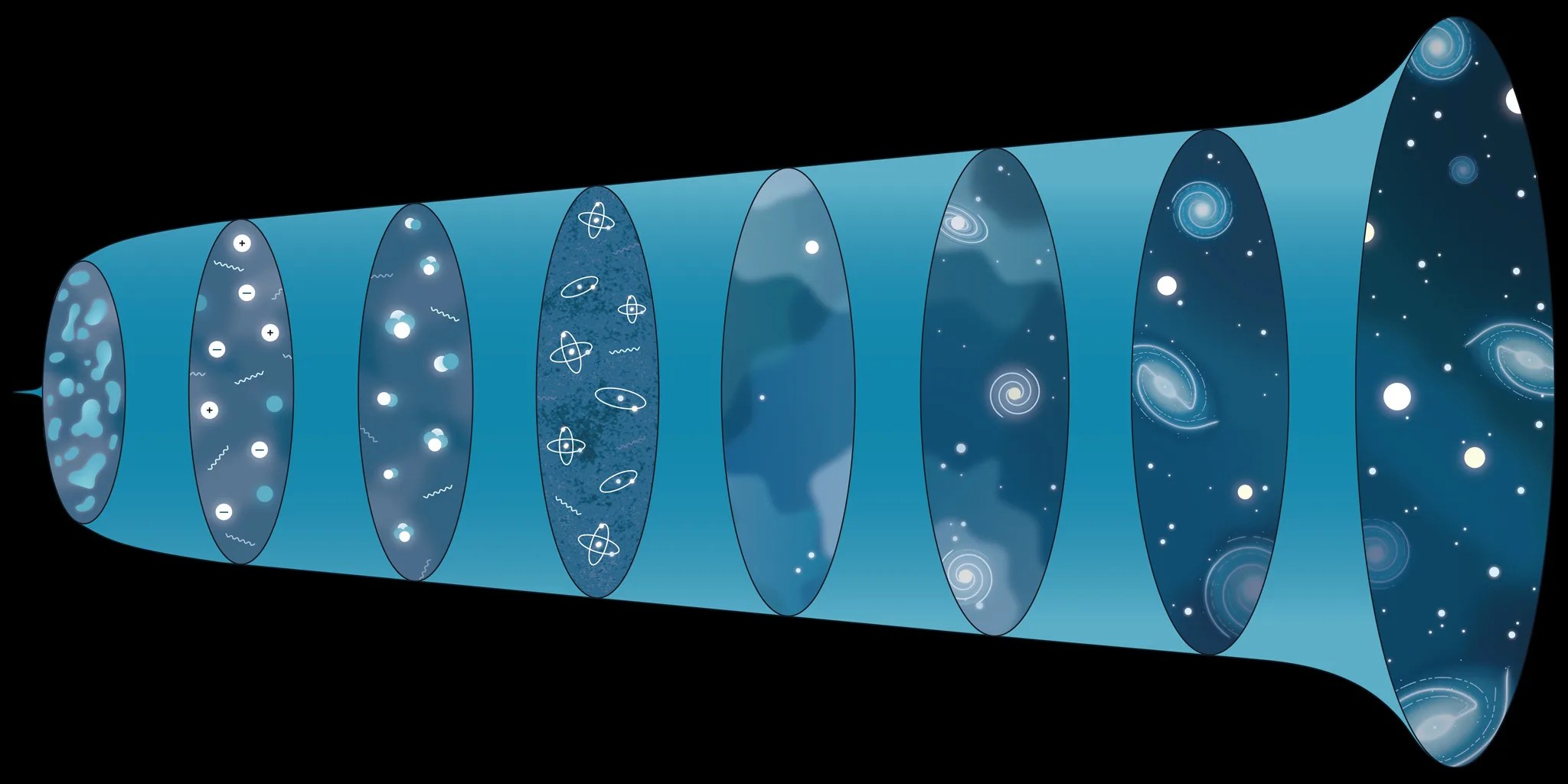

Scientists have identified over 1 million quasars, with the farthest one currently known lying about 13 billion light-years away. Since light takes time to travel, scientists can use light from these galaxies as a way to peer back in time to study black hole growth and galaxy evolution. Merging galaxies in the young universe may provide the fuel to power the enormous energy output of quasars, but when the feeding frenzy ends, the black hole cannot maintain it. It’s thought that quasar activity may be episodic and that this entire phase may last only about 10 million years.

Blazars

Blazars produce light across the electromagnetic spectrum. Their powerful jets point almost directly at Earth, so they appear brighter than other active galaxies. Observatories on Earth can sometimes detect high-energy particles – like neutrinos – produced within the jets and trace them back to their home galaxy. This information gives scientists a glimpse into the environment around the blazar’s supermassive black hole.